What to Write in Your Diary

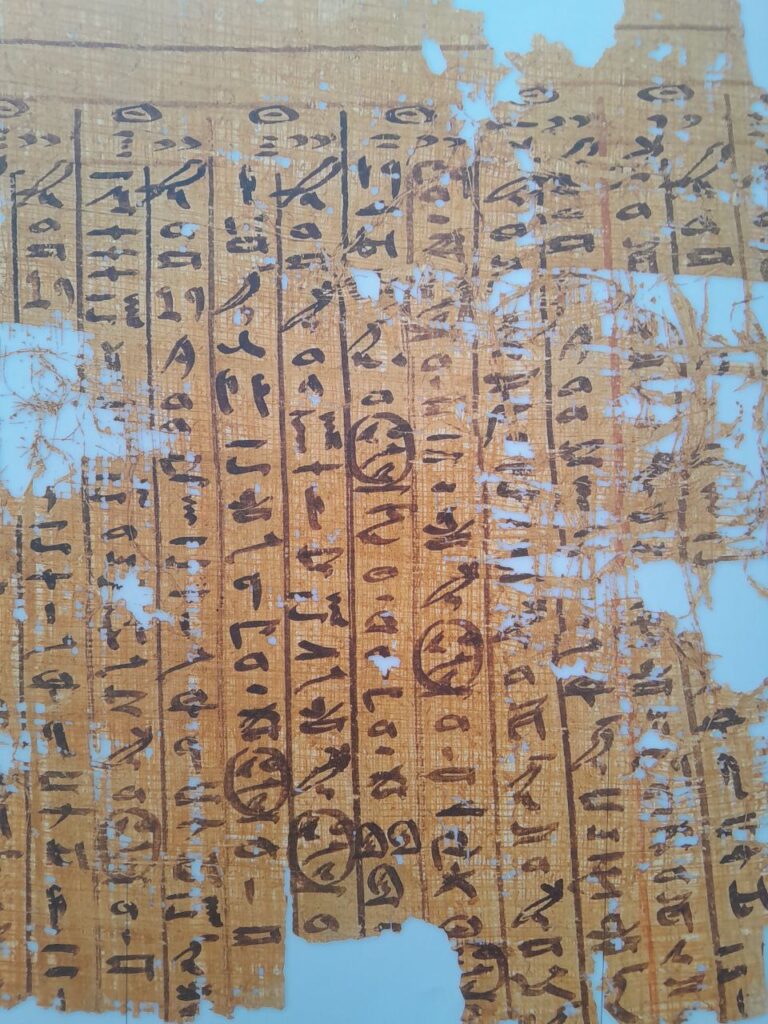

The Oldest Diary

The oldest diary ever found was written 4500 years ago in around the year 2552BC. It is the worklog of a foreman called Merer, who was involved in the building of the Great Pyramid at Giza. The diary covers five months, from July to November, and was discovered near the Red Sea by archaeologists in 2013.

The entries are short and full of unembellished facts:

Day 21: Merer spends the day with his [phyle] loading a transport ship-imu at Tura North, sets sail from Tura in the afternoon.

Day 22: Spends the night at Ro-She Khufu. In the morning, sets sail from Ro-She Kufu; sails towards Akhet-Kufu; spends the night at the Chapels of [Akhet] Khufu.

Building the Pyramids

The insight this brief account gives into the work involved in transporting the limestone blocks to Giza casts a whole new light on the pyramid. We suddenly see the pyramid from a human perspective; we see the individual blocks that were cut, transported and placed by countless human hands. All this because of a few terse sentences written by an Egyptian workman thousands of years ago.

Everything is Valuable

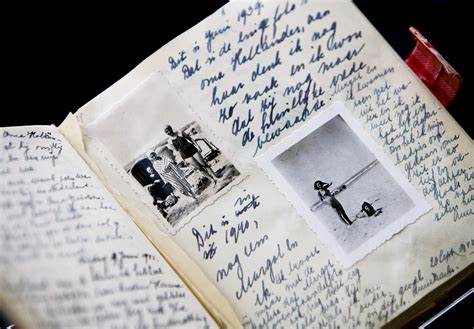

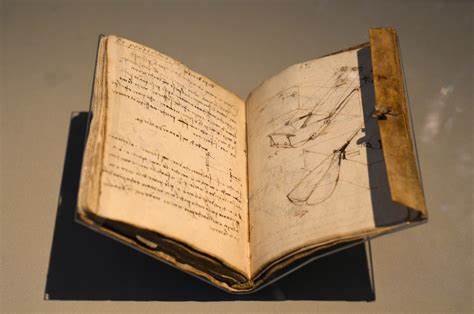

The ‘what’ of keeping a diary is often less important than the ‘if’ of keeping a diary. Anything we choose to record adds to the fabric of history. Over the centuries, diarists have recorded many various subjects, and each is important in its own way. From Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations to Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, to Anne Frank’s teenage diary, the written record benefits us all.

Be Part of History

The most important historical documents are those written at the time. These are called primary sources, and historians attach greater weight and value to these documents than to any other. Even those written soon after the event.

For example, a history of WWII written soon after the end of the war is vastly different in tone and content to a diary written as the events were unfolding. The diary gives us an invaluable insight into what was happening in real-time, and we get a glimpse into what people were thinking and hoping as they experienced events without the benefit of hindsight. There is nothing like reading a first-hand account of events or daily life.

Just Write

We can be part of this history writing; we can tell our stories and record the events in real-time and by doing so we help to maintain the integrity of the narrative. How do we do this? Just write. Write it all, write anything. It can be unembellished facts (à la Merer), or musings on life (like Marcus Aurelius). It can be a record of your daily minutiae or an account of world events from your perspective. All of us contribute to the bigger tapestry by adding our own stitches; the ‘tapestry of history’ would be the less without them.